An Author Reviewers Are Calling the Queen of Gothic Mystery

The Castle of Otranto (1764) is regarded as the first Gothic novel. The aesthetics of the book have shaped modern-twenty-four hour period gothic books, films, art, music and the goth subculture.[1]

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror in the 20th century, is a loose literary artful of fear and haunting. The name is a reference to Gothic architecture of the European Eye Ages, which was feature of the settings of early Gothic novels. The first piece of work to phone call itself Gothic was Horace Walpole's 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto, later subtitled "A Gothic Story". Subsequent 18th century contributors included Clara Reeve, Ann Radcliffe, William Thomas Beckford and Matthew Lewis. The Gothic likewise influenced verse past Samuel Taylor Coleridge and John Keats. Its 19th century successes include Mary Shelley'southward Frankenstein and piece of work past E. T. A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens. Later prominent works were Dracula by Bram Stoker, Richard Marsh's The Beetle and Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Instance of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Twentieth-century contributors include Daphne du Maurier, Stephen King, Shirley Jackson, Anne Rice and Toni Morrison.

Characteristics [edit]

Gothic fiction is characterized by an environs of fear, the threat of supernatural events, and the intrusion of the past upon the present.[two] [iii] Gothic fiction is distinguished from other forms of scary or supernatural stories, such as fairy tales, by the specific theme of the present being haunted by the past.[ii] [three] The setting typically includes physical reminders of the past, especially through ruined buildings which stand as proof of a previously thriving world which is decaying in the present.[four] Especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, characteristic settings include castles, religious buildings like monasteries and convents, and crypts.[2] The atmosphere is typically claustrophobic, and common plot elements include vengeful persecution, imprisonment, and murder.[2] The depiction of horrible events in Gothic fiction ofttimes serves equally a metaphorical expression of psychological or social conflicts.[3] Gothic fiction often moves between "high civilization" and "depression" or "popular civilisation".[3]

Role of architecture [edit]

Gothic literature is intimately associated with the Gothic Revival architecture of the same era. English Gothic writers often associated medieval buildings with what they saw as a dark and terrifying period, marked past harsh laws enforced past torture and with mysterious, fantastic, and superstitious rituals. Similar to the Gothic Revivalists' rejection of the clarity and rationalism of the neoclassical style of the Aware Establishment, the literary Gothic embodies an appreciation of the joys of extreme emotion, the thrills of fright and awe inherent in the sublime, and a quest for atmosphere. Gothic ruins invoke multiple linked emotions by representing inevitable disuse and the collapse of human creations – hence the urge to add fake ruins equally eyecatchers in English landscape parks.

Placing a story in a Gothic building serves several purposes. It inspires feelings of awe, implies that the story is set in the past, gives an impression of isolation or dissociation from the rest of the world, and coveys religious associations. Setting the novel in a Gothic castle was meant to imply a story not simply set in the past, but shrouded in darkness. The compages often served as a mirror for the characters and events of the story.[five] The buildings in The Castle of Otranto, for case, are riddled with tunnels that characters use to motility back and forth in cloak-and-dagger. This motion mirrors the secrets surrounding Manfred's possession of the castle and how information technology came into his family.[half dozen]

The Female Gothic [edit]

From the castles, dungeons, forests and subconscious passages of the Gothic novel genre emerged female Gothic. Guided by the works of authors such as Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley and Charlotte Brontë, the female Gothic allowed womens' societal and sexual desires to be introduced. In many respects, the novel's intended reader of the time was the adult female who, even every bit she enjoyed such novels, felt she had to "[lay] down her volume with affected indifference, or momentary shame,"[7] according to Jane Austen, author of Northanger Abbey. The Gothic novel shaped its form for woman readers to "plough to Gothic romances to find support for their own mixed feelings."[8]

Female Gothic narratives focus on such topics as a persecuted heroine in flying from a villainous father and in search of an absent-minded mother, while male writers tend towards masculine transgression of social taboos. The emergence of the ghost story gave women writers something to write near too the common matrimony plot, allowing them to present a more radical critique of male power, violence and predatory sexuality.[nine]

When the female Gothic coincides with the explained supernatural, the natural cause of terror is not the supernatural, only female disability and societal horrors: rape, incest, and the threatening command of a male adversary. Female Gothic novels also address women'due south discontent with patriarchal society, their problematic and unsatisfying maternal position, and their role within that society. Women's fears of entrapment in the domestic, their own torso, marriage, childbirth, or domestic abuse commonly announced in the genre.

Later the feature Gothic Bildungsroman-like plot sequence, female Gothic allowed readers to grow from "adolescence to maturity"[x] in the face up of the realized impossibilities of the supernatural. As protagonists like Adeline in The Romance of the Forest learn that their superstitious fantasies and terrors are replaced by natural cause and reasonable doubt, the reader may grasp the heroine'south true position: "The heroine possesses the romantic temperament that perceives strangeness where others run across none. Her sensibility, therefore, prevents her from knowing that her true plight is her condition, the inability of beingness female."[10]

History [edit]

Precursors [edit]

The components that would eventually combine into Gothic literature had a rich history past the fourth dimension Walpole presented a fictitious medieval manuscript in The Castle of Otranto in 1764.

Gothic literature is often described with words such as "wonder" and "terror."[xi] This sense of wonder and terror that provides the suspension of disbelief and so important to the Gothic—which, except for when it is parodied, fifty-fifty for all its occasional melodrama, is typically played straight, in a self-serious manner—requires the imagination of the reader to be willing to accept the thought that at that place might be something "beyond that which is immediately in forepart of us." The mysterious imagination necessary for Gothic literature to take gained any traction had been growing for some time before the appearance of the Gothic. The need for this came as the known earth was condign more explored, reducing the geographical mysteries of the world. The edges of the map were filling in, and no dragons were to be found. The human mind required a replacement.[12] Clive Bloom theorizes that this void in the collective imagination was disquisitional in the development of the cultural possibility for the rise of the Gothic tradition.[13]

The setting of most early Gothic works was medieval, merely this was a common theme long earlier Walpole. In Britain especially, there was a desire to reclaim a shared past. This obsession frequently led to extravagant architectural displays, such as Fonthill Abbey, and sometimes mock tournaments were held. Information technology was not but in literature that a medieval revival made itself felt, and this likewise contributed to a civilization set up to accept a perceived medieval work in 1764.[12]

The Gothic often uses scenery of disuse, decease, and morbidity to achieve its furnishings (particularly in the Italian Horror schoolhouse of Gothic). However, Gothic literature was not the origin of this tradition; indeed, it was far older. The corpses, skeletons, and churchyards so commonly associated with early Gothic works were popularized past the Graveyard Poets, and were also present in novels such as Daniel Defoe'due south Journal of the Plague Year, which contains comical scenes of plague carts and piles of corpses. Fifty-fifty before, poets like Edmund Spenser evoked a dreary and sorrowful mood in such poems equally Epithalamion.[12]

All of the aspects of pre-Gothic literature occur to some degree in the Gothic, but fifty-fifty taken together, they still fall short of true Gothic.[12] What was defective was an aesthetic to tie the elements together. Bloom notes that this artful must take the form of a theoretical or philosophical core, which is necessary to "sav[e] the best tales from becoming mere chestnut or incoherent sensationalism."[fourteen] In this instance, the artful needed to exist an emotional one, and was finally provided by Edmund Burke's 1757 work, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Cute, which "finally codif[ied] the gothic emotional feel."[fifteen] Specifically, Burke's thoughts on the Sublime, Terror, and Obscurity were nigh applicative. These sections tin be summarized thus: the Sublime is that which is or produces the "strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling"; the Sublime is well-nigh frequently evoked by Terror; and to cause Terror we need some amount of Obscurity – nosotros can't know everything nearly that which is inducing Terror – or else "a cracking deal of the apprehension vanishes"; Obscurity is necessary to experience the Terror of the unknown.[12] Bloom asserts that Burke's descriptive vocabulary was essential to the Romantic works that somewhen informed the Gothic.

The birth of Gothic literature was thought to have been influenced by political upheaval. Researchers linked its birth with the English Civil War, culminating in a Jacobite rebellion (1745) more recent to the offset Gothic novel (1764). A collective political memory and whatsoever deep cultural fears associated with information technology likely contributed to early Gothic villains as literary representatives of defeated Tory barons or Royalists "rise" from their political graves in the pages of early on Gothic novels to terrorize the bourgeois reader of late eighteenth century England.[16] [17] [18] [19]

Eighteenth-century Gothic novels [edit]

The commencement piece of work to call itself "Gothic" was Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764).[two] The first edition presented the story as a translation of a sixteenth century manuscript, and was widely popular. Walpole revealed himself as the true author in the 2d edition, which added the subtitle "A Gothic Story." The revelation prompted a backlash from readers, who considered information technology inappropriate for a modern writer to write a supernatural story in a rational age.[20] Walpole did not initially prompt many imitators. Beginning with Clara Reeve'south The Old English Baron (1778), the 1780s saw more writers attempting his combination of supernatural plots with emotionally realistic characters. Examples include Sophia Lee'southward The Recess (1783-five) and William Beckford'south Vathek (1786).[21]

At the height of the Gothic novel's popularity in the 1790s, the genre was almost synonymous with Ann Radcliffe, whose works were highly anticipated and widely imitated. Especially popular were The Romance of the Forest (1791) and The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794).[21] Radcliffe's novels were often seen every bit the feminine and rational opposite of a more violently horrifying male person Gothic associated with Matthew Lewis. Radcliffe's final novel, The Italian (1797), was a response to Lewis's The Monk (1796).[iii]

Other notable Gothic novels of the 1790s include William Godwin's Caleb Williams (1794), Regina Maria Roche's Clermont (1798), and Charles Brockden Brown's Wieland (1798), as well equally big numbers of bearding works published by the Minerva Printing.[21] In continental Europe, Romantic literary movements led to related Gothic genres such equally the German Schauerroman and the French roman noir.[22] [23] Eighteenth century Gothic novels were typically fix in a distant past and (for English novels) a afar European country, simply without specific dates or historical figures that characterized the later on evolution of historical fiction.[24]

The excesses, stereotypes, and frequent absurdities of the Gothic genre made it rich territory for satire.[25] Afterward 1800 there was a menses in which Gothic parodies outnumbered sincere Gothic novels.[26] In The Heroine by Eaton Stannard Barrett (1813), Gothic tropes are exaggerated for comic effect.[27] In Jane Austen'south novel Northanger Abbey (1818), the naive protagonist, much like a female Quixote, conceives herself a heroine of a Radcliffean romance and imagines murder and villainy on every side, though the truth turns out to be much more prosaic. This novel is also noted for including a list of early Gothic works since known as the Northanger Horrid Novels.[28]

2nd generation or Jüngere Romantik [edit]

The poetry, romantic adventures, and character of Lord Byron—characterised by his spurned lover Lady Caroline Lamb as "mad, bad and dangerous to know"—were another inspiration for the Gothic novel, providing the classic of the Byronic hero. Byron features every bit the title character in Lady Caroline's own Gothic novel Glenarvon (1816).

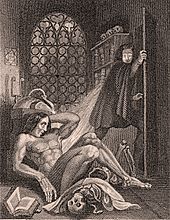

Byron was likewise the host of the historic ghost-story competition involving himself, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, and John William Polidori at the Villa Diodati on the banks of Lake Geneva in the summertime of 1816. This occasion was productive of both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and Polidori's The Vampyre (1819), featuring the Byronic Lord Ruthven. The Vampyre has been accounted by cultural critic Christopher Frayling every bit 1 of the most influential works of fiction ever written and spawned a craze for vampire fiction and theatre (and latterly film) that has not ceased to this day.[29] Mary Shelley'due south novel, though clearly influenced by the Gothic tradition, is frequently considered the first science fiction novel, despite the novel's lack of whatsoever scientific caption for the monster'due south animation and the focus instead on the moral dilemmas and consequences of such a creation.

John Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci (1819) and Isabella, or the Pot of Basil (1820) which feature mysteriously fey ladies.[thirty] In the latter poem, the names of the characters, the dream visions and the macabre physical details are influenced by the novels of premiere Gothicist Ann Radcliffe.[30]

A late case of a traditional Gothic novel is Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Maturin, which combines themes of anti-Catholicism with an outcast Byronic hero.[31] Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy! (1827) features standard Gothic motifs, characters, and plotting, simply with one significant twist: information technology is prepare in the twenty-second century and speculates on fantastic scientific developments that might have occurred four hundred years in the time to come, making it and Frankenstein among the earliest examples of the science fiction genre developing from Gothic traditions.[32]

During two decades, the most famous author of Gothic literature in Germany was the polymath E. T. A. Hoffmann. His novel The Devil's Elixirs (1815) was influenced by Lewis's The Monk and even mentions information technology. The novel explores the motive of Doppelgänger, a term coined by another German language author and supporter of Hoffmann, Jean Paul, in his humorous novel Siebenkäs (1796–1797). He also wrote an opera based on the Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's Gothic story Undine (1816), for which de la Motte Fouqué himself wrote the libretto.[33] Aside from Hoffmann and de la Motte Fouqué, 3 other of import authors from the era were Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (The Marble Statue, 1818), Ludwig Achim von Arnim (Die Majoratsherren, 1819), and Adelbert von Chamisso (Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte, 1814).[34] After them, Wilhelm Meinhold wrote The Bister Witch (1838) and Sidonia von Bork (1847).

In Spain, the priest Pascual Pérez Rodríguez was the most assidous novelist in the Gothic style, closely aligned to the supernatural explained by Ann Radcliffe.[35] At the aforementioned time, the poet José de Espronceda published The Student of Salamanca (1837-1840), a narrative poem which presents a horrid variation on the Don Juan fable.

In Russia, authors of the Romantic era include: Antony Pogorelsky (penname of Alexey Alexeyevich Perovsky), Orest Somov, Oleksa Storozhenko,[36] Alexandr Pushkin, Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy, Mikhail Lermontov (for his piece of work Stuss), and Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky.[37] Pushkin is particularly important, as his 1833 brusque story The Queen of Spades was so popular that it was adapted into operas and later films by both Russian and strange artists. Some parts of Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov's "A Hero of Our Fourth dimension" (1840) are also considered to belong in the Gothic genre, simply they lack the supernatural elements of other Russian Gothic stories.

The following poems are likewise now considered to belong to the Gothic genre: Meshchevskiy's "Lila", Katenin's "Olga", Pushkin'southward "The Bridegroom", Pletnev'southward "The Gravedigger" and Lermontov's "Demon" (1829–1839).[38]

The key author of the transition from Romanticism to Realism, Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol, who was likewise one of the most important authors of Romanticism, produced a number of works that qualify as Gothic fiction. Each of his three short story collections features a number of stories that fall within the Gothic genre or contain Gothic elements. They include "Saint John's Eve" and "A Terrible Vengeance" from Evenings on a Farm Nigh Dikanka (1831–1832), "The Portrait" from Arabesques (1835), and "Viy" from Mirgorod (1835). While all are well known, the latter is probably the most famous, having inspired at least eight film adaptations (ii now considered lost), one blithe film, two documentaries, and a video game. Gogol's work differs from Western European Gothic fiction, as his cultural influences drew on Ukrainian folklore, Cossack lifestyle and, equally he was a religious human, Orthodox Christianity.[39] [40]

Other relevant authors of this era include Vladimir Fyodorovich Odoevsky (The Living Corpse, written 1838, published 1844, The Ghost, The Sylphide, as well as short stories), Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (The Family of the Vourdalak, 1839, and The Vampire, 1841), Mikhail Zagoskin (Unexpected Guests), Józef Sękowski/Osip Senkovsky (Antar), and Yevgeny Baratynsky (The Ring).[37]

Nineteenth-century Gothic fiction [edit]

By the Victorian era, Gothic had ceased to be the dominant genre for novels in England, partly replaced by more than sedate historical fiction. Nevertheless, Gothic short stories continued to be pop, published in magazines or as modest chapbooks called penny dreadfuls.[2] The well-nigh influential Gothic writer from this period was the American Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote numerous short stories and poems reinterpreting Gothic tropes. His story "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) revisits classic Gothic tropes of aristocratic decay, death, and madness.[41] Poe is now considered the principal of the American Gothic.[ii] In England, i of the most influential penny dreadfuls is the anonymously authored Varney the Vampire (1847), which introduced the trope of vampires having sharpened teeth.[42] Some other notable English language writer of penny dreadfuls is George W. Chiliad. Reynolds, known for The Mysteries of London (1844), Faust (1846), Wagner the Wehr-wolf (1847) and The Necromancer (1857).[43] Elizabeth Gaskell's tales "The Doom of the Griffiths" (1858), "Lois the Witch", and "The Grey Adult female" all utilise 1 of the virtually mutual themes of Gothic fiction: the ability of ancestral sins to curse hereafter generations, or the fear that they will. In Spain, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer stood out with his romantic poems and brusque tales, some of them depicting supernatural events. Today he is considered past some equally the nearly-read writer in Spanish later Miguel de Cervantes.[44]

In addition to these brusk Gothic fictions were some novels which drew on the Gothic. Emily Brontë'due south Wuthering Heights (1847) transports the Gothic to the forbidding Yorkshire Moors and features ghostly apparitions and a Byronic hero in the person of the demonic Heathcliff. The Brontës' fictions were cited by feminist critic Ellen Moers as prime examples of Female Gothic, exploring woman'southward entrapment inside domestic space and subjection to patriarchal authority, and the transgressive and dangerous attempts to subvert and escape such restriction.[45] Emily's Cathy and Charlotte Brontë'south Jane Eyre are examples of female protagonists in such roles.[46] Louisa May Alcott'southward Gothic potboiler, A Long Fatal Beloved Chase (written in 1866, but published in 1995) is as well an interesting specimen of this subgenre. In addition to Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë'south Villette too shows Gothic influence. Similar other examples of the female Gothic, this book employs the explained supernatural. Throughout the book, a ghostly nun haunts the protagonist, Lucy Snowe. Lucy's friend, a doctor, suggests that the nun is a product of her imagination, but the finish of the book reveals that the nun was in fact a disguised suitor coming to visit Ginevra, a friend of Lucy's.[47] Some other Gothic feature of Villette is an anti-Catholic bias. Similar other gothic novels, such as Radcliffe's The Italian, information technology is set in a Catholic land. Lucy Snowe consistently says negative things about Catholicism in general and about specific Catholic people. Every bit an English Protestant, Lucy is very out of place in her Catholic setting.[48]

The genre was as well a heavy influence on mainstream writers such every bit Charles Dickens, who read Gothic novels as a teenager and incorporated their gloomy atmosphere and melodrama into his own works, shifting them to a more mod menses and an urban setting; for example in Oliver Twist (1837–1838), Bleak House (1854) and Neat Expectations (1860–1861). These works juxtapose wealthy, ordered and affluent civilisation with the disorder and barbarity of the poor in the same metropolis. Dour House in item is credited with introducing urban fog to the novel, which would become a frequent characteristic of urban Gothic literature and film (Mighall 2007). Miss Havisham from Groovy Expectations, a bitter recluse who shuts herself away in her gloomy mansion always since being jilted at the altar on her wedding ceremony day, is one of Dickens' most Gothic characters.[49] His most explicitly Gothic work is his concluding novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which he did non live to complete and was published unfinished upon his decease in 1870. The mood and themes of the Gothic novel held a particular fascination for the Victorians, with their obsession with mourning rituals, mementos, and mortality in general.

Irish Catholics also wrote Gothic fiction in the 19th century. Although some Anglo-Irish dominated and defined the subgenre decades later, they did not own it. Irish Catholic Gothic writers included Gerald Griffin, James Clarence Mangan, and John and Michael Banim. William Carleton was a notable Gothic writer, only he converted from Catholicism to Anglicanism during his life.[50]

In Germany, Jeremias Gotthelf wrote The Black Spider (1842), an allegorical work that uses Gothic themes. The last work from the German author Theodor Storm, The Passenger on the White Horse (1888), besides uses Gothic motives and themes.[51]

After Gogol, Russian literature saw the rising of Realism, but many authors continued to write stories within Gothic fiction territory. Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, one of the nigh historic Realists, wrote Faust (1856), Phantoms (1864), Vocal of the Triumphant Love (1881) and Clara Milich (1883). Another classic Russian Realist, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky, incorporated Gothic elements into many of his works, although none can be seen as purely Gothic.[52] Grigory Petrovich Danilevsky, who wrote historical and early on scientific discipline fiction novels and stories, wrote Mertvec-ubiytsa (Expressionless Murderer) in 1879. As well, Grigori Alexandrovich Machtet wrote "Zaklyatiy kazak", which may at present also be considered Gothic.[53]

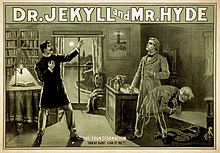

The 1880s saw the revival of the Gothic equally a powerful literary course centrolineal to fin de siecle, which fictionalized contemporary fears like ethical degeneration and questioned the social structures of the time. Archetype works of this Urban Gothic include Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Grey (1891), George du Maurier'south Trilby (1894), Richard Marsh's The Beetle (1897), Henry James' The Turn of the Screw (1898), and the stories of Arthur Machen.

In Republic of ireland, Gothic fiction tended to be purveyed by the Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy. Co-ordinate to literary critic Terry Eagleton, Charles Maturin, Sheridan Le Fanu, and Bram Stoker course the core of the Irish Gothic subgenre with stories featuring castles set in a barren landscape and a cast of remote aristocrats dominating an atavistic peasantry, which represent in allegorical form the political plight of Cosmic Republic of ireland subjected to the Protestant Ascendancy.[54] Le Fanu's use of the gloomy villain, forbidding mansion and persecuted heroine in Uncle Silas (1864) shows straight influence from both Walpole's Otranto and Radcliffe's Udolpho. Le Fanu'southward brusque story drove In a Drinking glass Darkly (1872) includes the superlative vampire tale Carmilla, which provided fresh blood for that item strand of the Gothic and influenced Bram Stoker's vampire novel Dracula (1897). Stoker'due south book not only created the most famous Gothic villain ever, Count Dracula, but also established Transylvania and Eastern Europe as the locus classicus of the Gothic.[55] Published in the aforementioned year as Dracula, Florence Marryat's The Blood of the Vampire is some other piece of vampire fiction. The Blood of the Vampire, which, like Carmilla, features a female vampire, is notable for its treatment of vampirism as both racial and medicalised. The vampire, Harriet Brandt, is besides a psychic vampire, killing unintentionally.[ citation needed ] [56]

In the United States, two notable late 19th century writers in the Gothic tradition were Ambrose Bierce and Robert W. Chambers. Bierce's short stories were in the horrific and pessimistic tradition of Poe. Chambers indulged in the decadent style of Wilde and Machen, even including a character named Wilde in his The King in Yellow (1895).[57] Some works of the Canadian writer Gilbert Parker also fall into the genre, including the stories in The Lane that Had No Turning (1900).[58]

The serialized novel The Phantom of the Opera (1909–1910) by the French author Gaston Leroux is another well-known example of Gothic fiction from the early 20th century, when many German authors were writing works influenced by Schauerroman, including Hanns Heinz Ewers.[59]

Russian Gothic [edit]

Until the 1990s, Russian Gothic was not viewed equally a genre or label by Russian critics. If used, the discussion "gothic" was used to describe (mostly early on) works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky from the 1880s. Most critics just used tags such as "Romanticism" and "fantastique", such equally in the 1984 story collection translated into English equally Russian 19th-Century Gothic Tales , merely originally titled Фантастический мир русской романтической повести, literally, "The Fantastic Globe of Russian Romanticism Short Story/Novella".[60] Withal, since the mid-1980s, Russian gothic fiction as a genre began to be discussed in books such as The Gothic-Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature, European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange 1760–1960, The Russian Gothic novel and its British antecedents and Goticheskiy roman five Rossii (The Gothic Novel in Russia).

The first Russian author whose work has been described as gothic fiction is considered to be Nikolay Mikhailovich Karamzin. While many of his works feature gothic elements, the offset considered to belong purely nether the gothic fiction label is Ostrov Borngolm (Island of Bornholm) from 1793.[61] Nearly ten years later on, Nikolay Ivanovich Gnedich followed suit with his 1803 novel Don Corrado de Gerrera, ready in Kingdom of spain in the reign of Philip Ii.[62] The term "Gothic" is sometimes also used to depict the ballads of Russian authors such as Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky, particularly "Ludmila" (1808) and "Svetlana" (1813), both translations based off Gottfreid August Burger's Gothic High german ballad, "Lenore".[63]

During the last years of Imperial Russian federation in the early 20th century, many authors continued to write in the Gothic fiction genre. They include the historian and historical fiction writer Alexander Valentinovich Amfiteatrov, Leonid Nikolaievich Andreyev, who developed psychological label, the symbolist Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov, Alexander Grinning, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov;[64] and Aleksandr Ivanovich Kuprin.[53] Nobel Prize winner Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin wrote Dry Valley (1912), which is seen as influenced by Gothic literature.[65] In a monograph on the subject, Muireann Maguire writes, "The centrality of the Gothic-fantastic to Russian fiction is nigh impossible to exaggerate, and certainly exceptional in the context of globe literature."[66]

Twentienth-century Gothic fiction [edit]

Gothic fiction and Modernism influenced each other. This is frequently axiomatic in detective fiction, horror fiction and science fiction, but the influence of the Gothic can also be seen in the high literary modernism of the 20th century. Oscar Wilde'due south The Picture of Dorian Greyness (1890) initiated a re-working of older literary forms and myths that becomes mutual in the piece of work of Yeats, Eliot, and Joyce, amongst others.[67] In Joyce's Ulysses (1922), the living are transformed into ghosts, which points to an Republic of ireland in stasis at the time, only as well a history of cyclical trauma from the Great Dearth in the 1840s through to the current moment in the text.[68] The mode Ulysses uses Gothic tropes such as ghosts and hauntings while removing the literally supernatural elements of 19th century Gothic fiction is indicative of a general form of modernist Gothic writing in the starting time half of the 20th century.

In America, pulp magazines such as Weird Tales reprinted classic Gothic horror tales from the previous century, by such authors every bit Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and printed new stories by mod authors featuring both traditional and new horrors.[69] The almost significant of these was H. P. Lovecraft who also wrote a conspectus of the Gothic and supernatural horror tradition in his Supernatural Horror in Literature (1936), besides every bit developing a Mythos that would influence Gothic and contemporary horror well into the 21st century. Lovecraft's protégé, Robert Bloch, contributed to Weird Tales and penned Psycho (1959), which drew on the archetype interests of the genre. From these, the Gothic genre per se gave way to modernistic horror fiction, regarded by some literary critics as a branch of the Gothic[70] although others utilise the term to cover the entire genre.

The Romantic strand of Gothic was taken up in Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938), which is seen by some to have been influenced by Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre.[71] Other books by du Maurier such every bit Jamaica Inn (1936) also display Gothic tendencies. Du Maurier's work inspired a substantial torso of "female Gothics", concerning heroines alternately swooning over or terrified by scowling Byronic men in possession of acres of prime real estate and the appertaining droit du seigneur.

Southern Gothic [edit]

The genre as well influenced American writing, creating a Southern Gothic genre that combines some Gothic sensibilities such as the grotesque with the setting and style of the Southern United States. Examples include Erskine Caldwell, William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, John Kennedy Toole, Manly Wade Wellman, Eudora Welty, Rhodi Militarist, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Flannery O'Connor, Davis Grubb, Anne Rice, Harper Lee and Cormac McCarthy.[72]

New Gothic romances [edit]

Mass-produced Gothic romances became popular in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s with authors such as Phyllis A. Whitney, Joan Aiken, Dorothy Eden, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, Mary Stewart, Alicen White and Jill Tattersall. Many featured covers showing a terror-stricken woman in diaphanous attire in front of a gloomy castle, ofttimes with a unmarried lit window. Many were published under the Paperback Library Gothic imprint and marketed to female person readers. While the authors were more often than not women, some men wrote Gothic romances under female pseudonyms: the prolific Clarissa Ross and Marilyn Ross were pseudonyms of the male Dan Ross; Frank Belknap Long published Gothics under his wife's name, Lyda Belknap Long; the British writer Peter O'Donnell wrote nether the pseudonym Madeleine Brent. Autonomously from imprints like Dearest Spell, discontinued in 2010, very few books seem to cover the term these days.[73]

Contemporary Gothic [edit]

Gothic fiction continues to exist extensively practised by contemporary authors.

Many modern writers of horror or other types of fiction exhibit considerable Gothic sensibilities – examples include Anne Rice, Stella Coulson, Susan Hill, Poppy Z. Brite and Neil Gaiman, and in some works past Stephen King.[74] [75] Thomas M. Disch's novel The Priest (1994) was subtitled A Gothic Romance, and partly modelled on Matthew Lewis' The Monk.[76] Many writers such equally Poppy Z. Brite, Stephen King and specially Clive Barker take focused on the surface of the body and the visuality of blood.[77] England's Rhiannon Ward is among recent writers of Gothic fiction.

Contemporary American writers in the tradition include Joyce Ballad Oates in such novels as Bellefleur and A Bloodsmoor Romance and short story collections such as Nighttime-Side (Skarda 1986b), and Raymond Kennedy in his novel Lulu Incognito.[ citation needed ]

A number of Gothic traditions have too developed in New Zealand (with the subgenre referred to equally New Zealand Gothic or Maori Gothic)[78] and Australia (known as Australian Gothic). These explore everything from the multicultural natures of the two countries[79] to their natural geography.[lxxx] Novels in the Australian Gothic tradition include Kate Grenville'south The Secret River and the works of Kim Scott.[81] An even smaller genre is Tasmanian Gothic, fix exclusively on the island, with prominent examples including Gould's Volume of Fish by Richard Flanagan and The Roving Party by Rohan Wilson.[82] [83] [84] [85]

Southern Ontario Gothic applies a similar sensibility to a Canadian cultural context. Robertson Davies, Alice Munro, Barbara Gowdy, Timothy Findley and Margaret Atwood have all produced notable exemplars of this form. Another author in the tradition was Henry Farrell, best known for his 1960 Hollywood horror novel What E'er Happened To Baby Jane? Farrell's novels spawned a subgenre of "Grande Matriarch Guignol" in the cinema, represented by such films every bit the 1962 pic based on Farrell's novel, which starred Bette Davis versus Joan Crawford; this subgenre of films was dubbed the "psycho-biddy" genre.

The many Gothic subgenres include a new "ecology Gothic" or "ecoGothic".[86] [87] [88] It is an ecologically aware Gothic engaged in "nighttime nature" and "ecophobia."[89] Writers and critics of the ecoGothic suggest that the Gothic genre is uniquely positioned to speak to anxieties most climate change and the planet'due south ecological future.[ninety]

Amongst the bestselling books of the 21st century, the YA novel Twilight by Stephenie Meyer, is now increasingly identified equally a Gothic novel, as is Carlos Ruiz Zafón'due south 2001 novel The Shadow of the Wind.[91]

Other media [edit]

Literary Gothic themes have been translated into other media.

There was a notable revival in 20th century Gothic horror cinema, such as the archetype Universal monsters films of the 1930s, Hammer Horror films, and Roger Corman's Poe cycle.[92]

In Hindi cinema, the Gothic tradition was combined with aspects of Indian civilization, particularly reincarnation, for an "Indian Gothic" genre, beginning with Mahal (1949) and Madhumati (1958).[93]

The 1960s Gothic television series Nighttime Shadows borrowed liberally from Gothic traditions, with elements similar haunted mansions, vampires, witches, doomed romances, werewolves, obsession and madness.

The early on 1970s saw a Gothic Romance comic book mini-trend with such titles as DC Comics' The Dark Mansion of Forbidden Love and The Sinister House of Hugger-mugger Love, Charlton Comics' Haunted Love, Curtis Magazines' Gothic Tales of Dear, and Atlas/Seaboard Comics' ane-shot magazine Gothic Romances.

Twentieth century rock music also had its Gothic side. Black Sabbath's 1970 debut album created a dark sound different from other bands at the fourth dimension and has been called the first ever "goth-rock" record.[94]

Even so, the start recorded apply of "gothic" to describe a style of music was for The Doors. Critic John Stickney used the term "gothic rock" to describe the music of The Doors in October 1967, in a review published in The Williams Tape.[95] The anthology recognized as initiating the goth music genre is Unknown Pleasures by the band Joy Division, although earlier bands such The Velvet Underground also contributed to the genre's distinctive way. Themes from Gothic writers such equally H. P. Lovecraft were used among Gothic rock and heavy metal bands, especially in black metal, thrash metal (Metallica'south The Call of Ktulu), decease metal, and gothic metal. For example, heavy metal musician King Diamond delights in telling stories total of horror, theatricality, Satanism and anti-Catholicism in his compositions.[96]

In role-playing games (RPG), the pioneering 1983 Dungeons & Dragons adventure Ravenloft instructs the players to defeat the vampire Strahd von Zarovich, who pines for his dead lover. It has been acclaimed every bit i of the best role-playing adventures of all fourth dimension and even inspired an entire fictional world of the same name. The World of Darkness is a gothic-punk RPG line set in the real world, with the added element of supernatural creatures such equally werewolves and vampires. In add-on to its flagship title Vampire: The Masquerade, the game line features a number of spin-off RPGs such as Werewolf: The Apocalypse, Mage: The Rising, Wraith: The Oblivion, Hunter: The Reckoning, and Changeling: The Dreaming, allowing for a broad range of characters in the gothic-punk setting. My Life with Primary uses Gothic horror conventions as a metaphor for abusive relationships, placing the players in the shoes of minions of a tyrannical, larger-than-life Primary.[97]

Diverse video games feature Gothic horror themes and plots. The Castlevania series typically involves a hero of the Belmont lineage exploring a nighttime, old castle, fighting vampires, werewolves, Frankenstein's Animal, and other Gothic monster staples, culminating in a battle confronting Dracula himself. Others, such as Ghosts'north Goblins, feature a camper parody of Gothic fiction. Resident Evil 7: Biohazard in 2017 involves an action hero and his wife trapped in a creepy plantation and mansion endemic past a family with sinister and hideous secrets, solving puzzles, fighting enemies, and a terrifying visions of a ghostly mutant in the shape of a trivial girl. This was followed past 2021's Resident Evil Village, a dark fantasy sequel focusing on a village under the control of a baroque Satanic cult, with werewolves, vampires and shapeshifters, solving puzzles and exploring secret passages, and a mysterious dollhouse where a dollmaker uses her powers through controlling dolls.

Popular tabletop card game Magic the Gathering, known for its parallel universe consisting of "planes", features the plane known equally Innistrad. Its full general aesthetic appears to exist based on northeast European Gothic horror. Cultists, ghosts, vampires, werewolves, and zombies are common denizens of Innistrad.

Modern Gothic horror films include Sleepy Hollow, Interview with the Vampire, Underworld, The Wolfman, From Hell, Dorian Grey, Let The Right One In, The Woman in Blackness, and Crimson Peak.

The TV series Penny Dreadful (2014–2016) brings many archetype Gothic characters together in a psychological thriller set in the dark corners of Victorian London.

The Oscar-winning Korean film Parasite has been called Gothic as well – specifically, Revolutionary Gothic.[98]

Recently, the Netflix original The Haunting of Colina House and its successor The Haunting of Bly Manor have integrated archetype Gothic conventions into modern psychological horror.[99]

Scholarship [edit]

Educators in literary, cultural, and architectural studies appreciate the Gothic as an area that facilitates investigation of the beginnings of scientific certainty. Every bit Ballad Senf has stated, "the Gothic was... a counterbalance produced by writers and thinkers who felt limited by such a confident worldview and recognized that the power of the past, the irrational, and the violent continue to hold sway in the world."[100] As such, the Gothic helps students amend sympathize their own doubts near the cocky-assurance of today'south scientists. Scotland is the location of what was probably the world'south kickoff postgraduate program to consider the genre exclusively: the MLitt in the Gothic Imagination at the University of Stirling, starting time recruited in 1996.[101]

See likewise [edit]

- American Gothic fiction

- Eighteenth-century Gothic novel

- French Revolution and the English Gothic Novel

- Gothic film

- Gothic romance picture show

- Gothic Western

- Irish gaelic Gothic literature

- List of gothic fiction works

- Southern Gothic

- Southern Ontario Gothic

- Suburban Gothic

- Tasmanian Gothic

- Urban Gothic

- Weird fiction

Notes [edit]

- ^ "The Castle of Otranto: The creepy tale that launched gothic fiction". BBC. Retrieved nine July 2017

- ^ a b c d e f g Birch, Dinah, ed. (2009). "Gothic fiction". The Oxford Companion to English language Literature (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN9780191735066.

- ^ a b c d e Hogle, Jerrold E., ed. (29 August 2002). "Introduction". The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1017/ccol0521791243. ISBN978-0-521-79124-3.

- ^ De Vore, David. "The Gothic Novel". Archived from the original on xiii March 2011.

The setting is greatly influential in Gothic novels. It not merely evokes the atmosphere of horror and dread, simply likewise portrays the deterioration of its earth. The decomposable, ruined scenery implies that at one fourth dimension there was a thriving world. At one fourth dimension the abbey, castle, or landscape was something treasured and appreciated. At present, all that lasts is the decaying shell of a once thriving dwelling.

- ^ Bayer-Berenbaum, L. 1982. The Gothic Imagination: Expansion in Gothic Literature and Art. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson Academy Press.

- ^ Walpole, H. 1764 (1968). The Castle of Otranto. Reprinted in 3 Gothic Novels. London: Penguin Printing.

- ^ "Austen's Northanger Abbey", 2nd Edition, Broadview, 2002.

- ^ Ronald "Terror Gothic: Nightmare and Dream in Ann Radcliffe and Charlotte Bronte", The Female person Gothic, Ed. Fleenor, Eden Press Inc., 1983.

- ^ Smith, Andrew, and Diana Wallace, "The Female Gothic: Then and Now." Gothic Studies, 25 August 2004, pp. 1–7.

- ^ a b Nichols "Place and Eros in Radcliffe", Lewis and Bronte, The Female Gothic, ed. Fleenor, Eden Printing Inc., 1983.

- ^ "Terror and Wonder the Gothic Imagination". The British Library. British Library. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Early and Pre-Gothic Literary Conventions & Examples". Spooky Scary Skeletons Literary and Horror Social club. Spooky Scary Society. 31 October 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Blossom, Clive (2010). Gothic Histories: The Sense of taste for Terror, 1764 to Nowadays. London: Continuum International Publishing Grouping. p. 2.

- ^ Blossom, Clive (2010). Gothic Histories: The Gustation for Terror, 1764 to Present. London: Continuum International Publishing Grouping. p. 8.

- ^ "Early and Pre-Gothic Literary Conventions & Examples". Chilling Scary Skeletons Literary and Horror Society. Spooky Scary Society. 31 Oct 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Radcliffe, Ann (1995). The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne. Oxford: Oxford Up. pp. seven–xxiv. ISBN0192823574.

- ^ Alexandre-Garner, Corinne (2004). Borderlines and Borderlands:Confluences XXIV. Paris: University of Paris Ten-Nanterre. pp. 205–216. ISBN2907335278.

- ^ Cairney, Christophe r (1995). The Villain Graphic symbol in the Puritan World. Columbia: Academy of Missouri. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Cairney, Chris (2018). "Intertextuality and Intratextuality; Does Mary Shelley 'Sit Heavily Behind' Conrad's Center of Darkness?" (PDF). Civilization in Focus. one (1): 92. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Clery, Due east. J. (1995). The Ascension of Supernatural Fiction, 1762-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-511-51899-7. OCLC 776946868.

- ^ a b c Sucur, Slobodan (half dozen May 2007). "Gothic fiction". The Literary Encyclopedia. ISSN 1747-678X.

- ^ Hale, Terry (2002), Hogle, Jerrold E. (ed.), "French and High german Gothic: the beginnings", The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction, Cambridge Companions to Literature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing, pp. 63–84, ISBN978-0-521-79124-three , retrieved 2 September 2020

- ^ Seeger, Andrew Philip (ane January 2004). "Crosscurrents between the English Gothic novel and the German Schauerroman". ETD Drove for University of Nebraska - Lincoln: 1–208.

- ^ Richter, David H. (28 July 2016). Downie, James Alan (ed.). The Gothic Novel and the Lingering Appeal of Romance. Oxford University Press. pp. 471–488. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566747.013.021. ISBN978-0-19-956674-vii.

- ^ Skarda 1986.

- ^ Potter, Franz J. (2005). The history of Gothic publishing, 1800-1835 : exhuming the trade. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN1-4039-9582-6. OCLC 58807207.

- ^ Horner, Avril (2005). Gothic and the comic turn. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN978-0-230-50307-6. OCLC 312477942.

- ^ Wright (2007), pp. 29-32.

- ^ Frayling, Christopher (1992) [1978]. Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula. London: Faber. ISBN978-0-571-16792-0.

- ^ a b Skarda and Jaffe (1981), pp. 33–35 and 132–133.

- ^ Varma 1986

- ^ Lisa Hopkins, "Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy!: Mary Shelley Meets George Orwell, and They Go in a Balloon to Egypt", in Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text, 10 (June 2003). Cf.ac.uk (25 January 2006). Retrieved on xviii September 2018.

- ^ Hogle, p. 105–122.

- ^ Cusack, Barry, p. 91, pp. 118–123.

- ^ Aldana, Xavier, pp. x–17

- ^ Krys Svitlana, "Folklorism in Ukrainian Gotho-Romantic Prose: Oleksa Storozhenko's Tale About Devil in Love (1861)." Folklorica: Journal of the Slavic and E European Folklore Association, xvi (2011), pp. 117–138.

- ^ a b Horner (2002). Neil Cornwell: European Gothic and the 19th-century Gothic literature, pp. 59–82.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). Michael Pursglove: Does Russian gothic verse exist, pp. 83–102.

- ^ Simpson, c. p. 21.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). Neil Cornwell, pp. 189–234.

- ^ (Skarda and Jaffe (1981) pp. 181–182.

- ^ "Did Vampires Not Have Fangs in Movies Until the 1950s?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Baddeley (2002) pp. 143–144.)

- ^ "Bécquer es el escritor más leído después de Cervantes". La Provincia. Diario de las Palmas (in Spanish). 28 July 2011. Retrieved 22 Feb 2018.

- ^ Moers, Ellen (1976). Literary Women. Doubleday. ISBN9780385074278.

- ^ Jackson (1981) pp. 123–129.

- ^ Johnson, E. D. H. "'Daring the Dread Glance': Charlotte Brontë'south Handling of the Supernatural in Villette." Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 20, no. 4, University of California Press, 1966, pp. 325–36, https://doi.org/x.2307/2932664.

- ^ Clarke, Micael M. "Charlotte Bronte'due south 'Villette', Mid-Victorian Anti-Catholicism, and the Turn to Secularism." ELH, vol. 78, no. 4, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, pp. 967–89, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41337561.

- ^ "The Gothic in Slap-up Expectations". British Library. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Killeen, Jarlath (31 January 2014). The Emergence of Irish Gothic Fiction. Edinburgh University Press. p. 51. doi:ten.3366/edinburgh/9780748690800.001.0001. ISBN978-0-7486-9080-0.

- ^ Cusack, Barry, p. 26.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). pp. 211–256.

- ^ a b Butuzov.

- ^ Eagleton, 1995.

- ^ Mighall, 2003.

- ^ Haefele-Thomas, Ardel (2012). Queer Others in Victorian Gothic: Transgressing Monstrosity. Cardiff: University of Wales Printing. pp. 108–111, 117–118. ISBN9780708324660.

- ^ Punter, David (1980). "Later American Gothic". The Literature of Terror: A History of Gothic Fictions from 1765 to the Nowadays Mean solar day. United Kingdom: Longmans. pp. 268–290. ISBN9780582489219.

- ^ Rubio, Jen (2015). "Introduction" to The Lane that Had No Turning, and Other Tales Concerning the People of Pontiac. Oakville, ON: Rock'southward Mills Printing. pp. vii–viii. ISBN978-0-9881293-7-5.

- ^ Cusack, Barry, p. 23.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). Introduction.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). Derek Offord: Karamzin'southward Gothic Tale, pp. 37–58.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). Alessandra Tosi: "At the origins of the Russian gothic novel", pp. 59–82.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). Michael Pursglove: "Does Russian gothic verse exist?" pp. 83–102.

- ^ Cornwell (1999). p. 257.

- ^ Peterson, p. 36.

- ^ Muireann Maguire, Stalin's Ghosts: Gothic Themes in Early on Soviet Literature (Peter Lang Publishing, 2012; ISBN 3-0343-0787-10), p. 14.

- ^ Hansen, Jim (2011). "A Nightmare on the Encephalon: Gothic Suspicion and Literary Modernism". Literature Compass. 8 (9): 635–644. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00763.x.

- ^ Wurtz, James F. (2005). "Scarce More a Corpse: Famine Retentiveness and Representations of the Gothic in Ulyssses". Journal of Modern Literature. 29: 102–117. doi:ten.2979/JML.2005.29.i.102. ProQuest 201671206.

- ^ Goulart (1986)

- ^ (Wisker (2005) pp232-33)

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (16 March 2004). "Du Maurier'south 'Rebecca,' A Worthy 'Eyre' Apparent". The Washington Post.

- ^ Skarda and Jaffe (1981), pp. 418–456.)

- ^ "Open Library On Internet Archive".

- ^ Skarda and Jaffe (1981) pp. 464–465 and 478.

- ^ Davenport-Hines (1998) pp. 357-358).

- ^ Linda Parent Lesher, The Best Novels of the Nineties: A Reader's Guide. McFarland, 2000 ISBN 0-7864-0742-five, p. 267.

- ^ Stephanou, Aspasia, Reading Vampire Gothic Through Blood, Palgrave, 2014.

- ^ Kavka, Misha (16 October 2014). The Gothic and the everyday: living Gothic. pp. 225–240. ISBN978-1-137-40664-4.

- ^ "Hello Darkness: New Zealand Gothic". robertleonard.org . Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Wide Open up Fear: Australian Horror and Gothic Fiction". This Is Horror. ten January 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Doolan, Emma. "Australian Gothic: from Hanging Stone to Nick Cave and Kylie, this genre explores our dark side". The Chat . Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Sussex, Lucy (27 June 2019). "Rohan Wilson's adventurous experiment with climate-modify fiction". The Sydney Morn Herald.

The upshot is a book that while with one pes in Tasmanian Gothic, does correspond a personal innovation.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Holgate, Ben (2014). "The Impossibility of Knowing: Developing Magical Realism's Irony in Gould's Book of Fish". Journal of the Association for the Report of Australian Literature (JASAL). 14 (ane). ISSN 1833-6027.

On ane level, the book is a picaresque romp through colonial Tasmania in the early 1800s based on the not very reliable reminiscences of Gould, a convicted forger, painter of fish and inveterate raconteur. On another level, the novel is a Gothic horror tale in its reimagining of a violent, brutal and oppressive penal colony whose militaristic regime subjugated both the imported and original inhabitants.

- ^ Britten, Naomi; Trilogy, Mandala; Bird, Carmel (2010). "Re-imagining the Gothic in Gimmicky Commonwealth of australia: Carmel Bird Discusses Her Mandala Trilogy". Antipodes. 24 (1): 98–103. ISSN 0893-5580. JSTOR 41957860 – via JSTOR.

Richard Flanagan, Gould's Book of Fish, would take to be Gothic. Tasmanian history is pro-foundly dark and dreadful.

- ^ Derkenne, Jamie (2017). "Richard Flanagan'due south and Alexis Wright's Magic Nihilism". Antipodes. 31 (2): 276–290. doi:10.13110/antipodes.31.two.0276. ISSN 0893-5580. JSTOR 10.13110/antipodes.31.2.0276.

Flanagan in Gould's Book of Fish and Wanting also seeks to interrogate assumed complacency through a strangely comic and dark rerendering of reality to draw out many truths, such as Tasmania'southward treatment of its Indigenous peoples.

- ^ says, Max (23 November 2014). "The Ecogothic".

- ^ Hillard, Tom. "'Deep Into That Darkness Peering': An Essay on Gothic Nature". Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 16 (4), 2009.

- ^ Smith, Andrew and William Hughes. "Introduction: Defining the ecoGothic" in EcoGothic. Andrew Smith and William Hughes, eds. Manchester Academy Press. 2013.

- ^ Simon Estok, "Theorizing in a Infinite of Clashing Openness: Ecocriticism and Ecophobia", Literature and Environment, 16 (2), 2009; Simon Estok, The Ecophobia Hypothesis, Routledge, 2018.

- ^ See "ecoGothic" in William Hughes, Central Concepts in the Gothic. Edinburgh Academy Press, 2018: 63.

- ^ Edwards, Justin; Monnet, Agnieszka. The Gothic in Gimmicky Literature and Popular Civilization: Pop Goth. Taylor and Francis. ISBN9781136337888.

- ^ Davenport-Hines (1998) pp355-8)

- ^ Mishra, Vijay (2002). Bollywood cinema: temples of desire. Routledge. pp. 49–57. ISBN0-415-93014-6.

- ^ Baddeley (2002) p. 264.

- ^ Stickney, John (24 October 1967). "Four Doors to the Future: Gothic Stone Is Their Thing". The Williams Record. Archived from the original on four May 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ Baddeley (2002) p. 265.

- ^ Darlington, Steve (8 September 2003). "Review of My Life with Main". RPGnet . Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Southard, Connor (xx November 2019). "'Parasite' and the rise of Revolutionary Gothic". theoutline.com . Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Romain, Lindsey (5 Oct 2020). "THE HAUNTING OF BLY MANOR Is a Beautiful Gothic Romance". Nerdist . Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Carol Senf, "Why We Need the Gothic in a Technological World," in: Humanistic Perspectives in a Technological World, ed. Richard Utz, Valerie B. Johnson, and Travis Denton (Atlanta: School of Literature, Media, and Communication, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2014), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Hughes, William (2012). Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature. Scarecrow Press.

References [edit]

- Aldana Reyes, Xavier (2017). Castilian Gothic: National Identity, Collaboration and Cultural Accommodation. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN978-1137306005.

- Baddeley, Gavin (2002). Goth Chic. London: Plexus. ISBN978-0-85965-382-iv.

- Baldick, Chris (1993), Introduction, in The Oxford Volume of Gothic Tales, Oxford: Oxford University Printing

- Birkhead, Edith (1921), The Tale of Terror

- Bloom, Clive (2007), Gothic Horror: A Guide for Students and Readers, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Botting, Fred (1996), Gothic, London: Routledge

- Brown, Marshall (2005), The Gothic Text, Stanford, CA: Stanford UP

- Butuzov, A.E. (2008), Russkaya goticheskaya povest Nineteen Veka

- Charnes, Linda (2010), Shakespeare and the Gothic Strain, Vol. 38, pp. 185

- Clery, Due east.J. (1995), The Rise of Supernatural Fiction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cornwell, Neil (1999), The Gothic-Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature, Amsterdam: Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, Studies in Slavic Literature and Poetics, volume 33

- Melt, Judith (1980), Women in Shakespeare, London: Harrap & Co. Ltd

- Cusack A., Barry M. (2012), Popular Revenants: The High german Gothic and Its International Reception, 1800–2000, Camden Firm

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (1998), Gothic: 400 Years of Backlog, Horror, Evil and Ruin, London: Fourth Estate

- Davison, Carol Margaret (2009), Gothic Literature 1764–1824, Cardiff: Academy of Wales Printing

- Drakakis, John & Dale Townshend (2008), Gothic Shakespeares, New York: Routledge

- Eagleton, Terry (1995), Heathcliff and the Great Hunger, New York: Verso

- Fuchs, Barbara (2004), Romance, London: Routledge

- Gamer, Michael (2006), Romanticism and the Gothic. Genre, Reception and Canon Formation, Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press

- Gibbons, Luke (2004), Gaelic Gothic, Galway: Arlen Firm

- Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar (1979), The Madwoman in the Attic. ISBN 0-300-08458-7

- Goulart, Ron (1986), "The Pulps" in Jack Sullivan, ed., The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 337-xl

- Grigorescu, George (2007), Long Journeying Inside The Flesh, Bucharest, Romania ISBN 978-0-8059-8468-two

- Hadji, Robert (1986), "Jean Ray" in Jack Sullivan, ed., The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural

- Haggerty, George (2006), Queer Gothic, Urbana, IL: Illinois Upwardly

- Halberstam, Jack (1995), Pare Shows, Durham, NC: Duke Upward

- Hogle, J.E. (2002), The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction, Cambridge Academy Press

- Horner, Avril & Sue Zlosnik (2005), Gothic and the Comic Plow, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Horner, Avril (2002), European Gothic: A Spirited Substitution 1760–1960, Manchester & New York: Manchester Academy Press

- Hughes, William, Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature, Scarecrow Press, 2012

- Jackson, Rosemary (1981), Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion

- Kilgour, Maggie (1995), The Rising of the Gothic Novel, London: Routledge

- Jürgen Klein (1975), Der Gotische Roman und die Ästhetik des Bösen, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft

- Jürgen Klein, Gunda Kuttler (2011), Mathematik des Begehrens, Hamburg: Shoebox Business firm Verlag

- Korovin, Valentin I. (1988), Fantasticheskii mir russkoi romanticheskoi povesti

- Medina, Antoinette (2007), A Vampires Vedas

- Mighall, Robert (2003), A Geography of Victorian Gothic Fiction: Mapping History's Nightmares, Oxford: Oxford Academy Printing

- Mighall, Robert (2007), "Gothic Cities", in C. Spooner and E. McEvoy, eds, The Routledge Companion to Gothic, London: Routledge, pp. 54–72

- O'Connell, Lisa (2010), The Theo-political Origins of the English Marriage Plot, Novel: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 43, Issue one, pp. 31–37

- Peterson, Dale (1987), The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring, 1987), pp. 36–49

- Punter, David (1996), The Literature of Terror, London: Longman (ii volumes)

- Punter, David (2004), The Gothic, London: Wiley-Blackwell

- Sabor, Peter & Paul Yachnin (2008), Shakespeare and the Eighteenth Century, Ashgate Publishing Ltd

- Salter, David (2009), This demon in the garb of a monk: Shakespeare, the Gothic and the discourse of anti-Catholicism, Vol. 5, Issue i, pp. 52–67

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1986), The Coherence of Gothic Conventions, NY: Methuen

- Shakespeare, William (1997), The Riverside Shakespeare: Second Edition, Boston, NY: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Simpson, Mark S. (1986), The Russian Gothic Novel and its British Antecedents, Slavica Publishers

- Skarda, Patricia L., and Jaffe, Norma Crow (1981), Evil Image: Two Centuries of Gothic Brusk Fiction and Poetry. New York: Meridian

- Skarda, Patricia (1986), "Gothic Parodies" in Jack Sullivan ed. (1986), The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 178-ix

- Skarda, Patricia (1986b), "Oates, Joyce Carol" in Jack Sullivan ed. (1986), The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 303-four

- Stevens, David (2000), The Gothic Tradition, ISBN 0-521-77732-i

- Sullivan, Jack, ed. (1986), The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural

- Summers, Montague (1938), The Gothic Quest

- Townshend, Dale (2007), The Orders of Gothic

- Varma, Devendra (1957), The Gothic Flame

- Varma, Devendra (1986), "Maturin, Charles Robert" in Jack Sullivan, ed., The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 285-286

- Wisker, Gina (2005), Horror Fiction: An Introduction, Continuum: New York

- Wright, Angela (2007), Gothic Fiction, Basingstoke: Palgrave

External links [edit]

-

Works related to Gothic fiction at Wikisource

Works related to Gothic fiction at Wikisource - Gothic Fiction at the British Library

- Key motifs in Gothic Fiction – a British Library film

- Gothic Fiction Bookshelf at Project Gutenberg

- Irish Periodical of Gothic and Horror Studies

- Gothic author biographies

- The Gothic Imagination Archived 18 December 2017 at the Wayback Automobile

- "Gothic", In Our Time, BBC Radio 4 word with Chris Baldick, A.N. Wilson and Emma Clery (January. iv, 2001)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gothic_fiction

0 Response to "An Author Reviewers Are Calling the Queen of Gothic Mystery"

Post a Comment